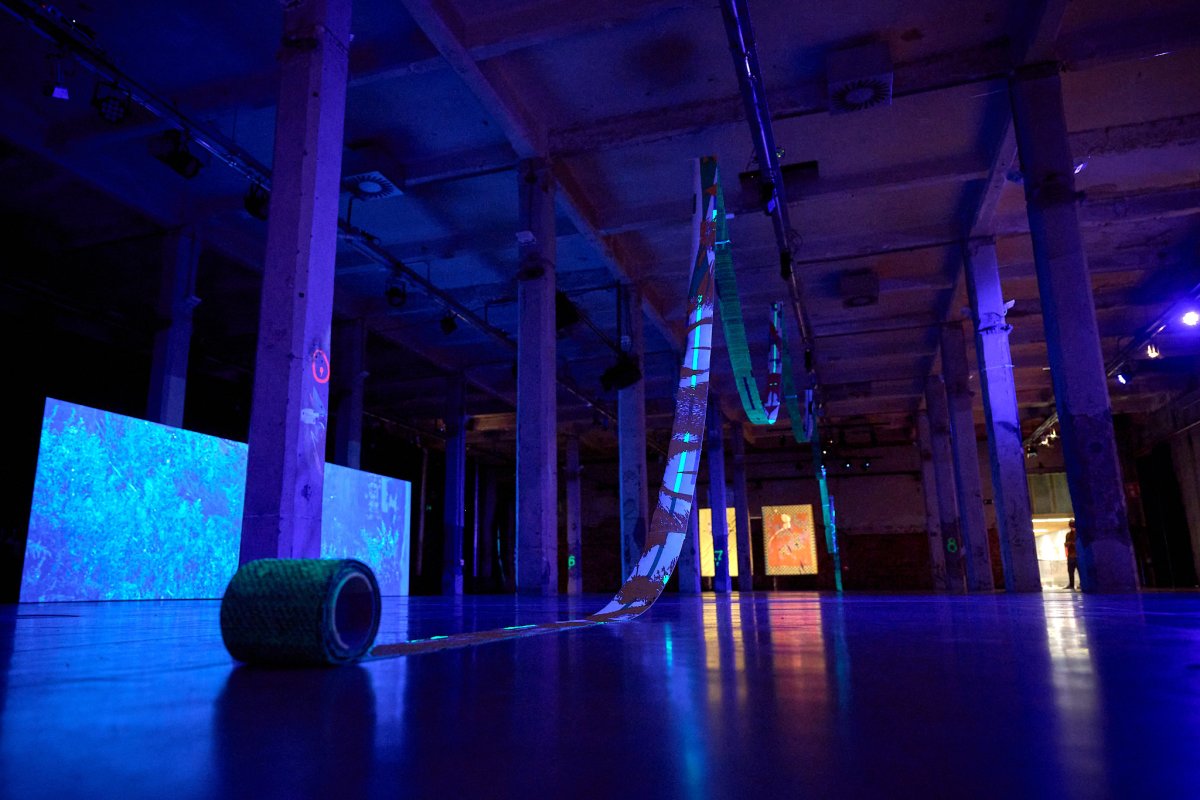

inverse gravity and teslaforming

An interview with Bani Brusadin about his curatorial practice and the need for a new language to capture technology's speed and strangeness.

What does this classification of the “Unsupported Media Type” mean to you?

As a tag line "Unsupported Media Types" tells different stories at once. The first one is about a very long and diverse heritage of people – artists, scientists, designers, activists, architects, musicians, performers, and citizens in general – who felt attracted by technologies that they were perceiving as media, that is: as forms of mediation between situations, or people, or geographies, or even between different forms of intelligence beyond the human. Their interests, often ignored by academia and established milieus, led to discoveries, unconventional assemblages, and visionary coalitions.

Today, Unsupported Media Types also speaks to a digital landscape now fully legitimized and industrialized, where online creators and the gaming industry rival legacy media in reach and resources. Under these relatively new circumstances, Unsupported Media Types comes to mean a field of action that is not struggling for recognition in museums or universities anymore, but is rather fighting for techno-diversity in an increasingly top-down, monopolistic technological regime.

We should probably pay attention to Unsupported Media Types to detect vectors of change, for better or worse.

From these two stories, a third one emerges: Unsupported Media Types can be understood as multi-scalar entanglements – networks of devices, infrastructures, protocols, lifeforms, and societies – that help us make sense of the complexities of the 21st century. Rather than imposing human concepts to steer technology towards good “ethical” ends (whose ethics, after all?), we should probably pay attention to Unsupported Media Types to detect vectors of change, for better or worse. In this sense, Unsupported Media Types become techno-cultural and techno-political assemblages that signal the need for a fundamental update of how human society is organized on this planet. By understanding technology in this way, we gain deeper insight into personal, social, and planetary challenges – from ecology and democracy to power, solidarity, and progress. In other words, we should approach Unsupported Media Types as key partners in rethinking and radically expanding the humanistic perspective.

What concepts are you currently interested in?

Currently, I’m working on two concepts: inverse gravity and teslaforming. The first helped me see why abandoned mining sites in Northern Croatia remain relevant beyond their industrial decay. While curating the Industrial Art Biennial with Giulia Colletti for Labin Art Express, I kept asking: what does “industrial” mean today, and how does it relate to the remnants of 20th-century extraction? If energy transactions are a planetary metabolism where human labor exploits other agents, what’s the real metabolic meaning of the force, the sweat (and often blood and death) that made mining possible?

Though 21st-century industry has radically changed form, it still accelerates the same processes. Inverse gravity becomes a way to look beyond ruins – a desire for transcendence shared by oligarchs chasing immortality and by artists, technologists, and activists imagining new cultural and technological “stacks.” Materially impossible, it’s also a shift in perspective that redefines what is “above” or “below,” transforming exploitation into solidarity.

As technological power evolves faster than we can comprehend, new language is needed to capture its speed and strangeness.

The second concept I’ve been developing at Medialab Matadero is teslaforming. As technological power evolves faster than we can comprehend, new language is needed to capture its speed and strangeness. Teslaforming – a fusion of terraforming and today’s socio-technical fetishes – is my provisional term. Inspired by Benjamin Bratton’s The Stack and Bahar Noorizadeh’s Teslaism, it is not a production model or specific technology but a way to describe interconnected phenomena across different layers of society that feed back on each other in disproportionate and often monstrous ways.

Teslaforming serves as a conceptual shortcut to trace systemic transformations that, while seemingly about technology, are reshaping social, aesthetic, and political life – hidden in plain sight and moving at unprecedented speed. It can be mapped through four coordinates: 1) Extremophile technological narratives, 2) Revolutionary architectures and utopian energies, 3) Propaganda resembling LARP or shitposting, 4) Premium democracy and emerging political spectrums.

While each of these coordinates has deep roots in Western society, the novelty of the phenomenon I call teslaforming lies in the structural relationships between these vectors: instead of operating in separate spheres of society, these layers feedback on each other in a systematic and unprecedented way, amplifying both their effectiveness and the perception of general instability. Teslaforming is a concept that, like a sensor, allows us to detect these tectonic movements. It provides me with a framework for investigating these vectors of volatility, both controlled and out of control, and analysing how they are conceived, executed and interconnected.

What kind of responsibilities and/or relationships does your curatorial practice entail?

This is a hard question mainly because I guess that – beyond the basic core values of respect, integrity, trust, and mutual care – responsibilities and relationships are always built in context. As a self-taught curator, I would say that I instinctively conceive my job as developing situations that allow for collective intellectual pleasure. Now, concepts or theoretical positions naturally stem from that very basic principle and the contexts I try to engage with and be part of. While always acknowledging my personal limitations (even those inherited through my own privileges), I live my role as someone who tries to use his experience to make connections that others are not seeing, or detecting. Ideas, desires, goals that are not receiving the attention they deserve, sometimes because they question real social hierarchies or because they come from someone who is either not legitimised or even marginalized. I understand my role as a mediator, avid learner and bricoleur. I guess this is a nicer way to say that I feel naturally attracted to people who might not be able to sit in the same room without fighting with each other: artists, including both superpro artists and early career ones who have no clue about what they’re doing; geeks; social justice fighters; journalists; policy makers; poets. I like to keep that threshold between the insider and the outsider open for trespassing, in both directions.

I would say that I instinctively conceive my job as developing situations that allow for collective intellectual pleasure.

What are the local conditions you are working in?

In Spain’s largest cities, where I currently work, audiences are often curious, motivated and well-prepared. Art and design schools, despite organizational dysfunctions, can be fertile testing grounds for new and radical ideas and practices. Funding exists but is unstable and rarely supports long-term careers. Combined with a weak job market and a huge housing crisis, this results in widespread talent but few opportunities for sustained research or ambitious projects, leaving artists, technologists and activists tied to precarious income. In this context, cross-disciplinary work is for me and my organization both an intellectual imperative and a practical strategy, though reaching marginalized communities remains a challenge.

Has the internet failed us?

Corporate, broligarch internet? Yes, big time. Yet, other versions of the internet, including the original vision of a huge, peer-to-peer network of devices and people, are still burning under the ashes and still inspire artists, grassroots initiatives, and even policymakers in Europe and elsewhere. What is not clear at the moment is whether the internet as we know it will still be relevant or just turn into a boundless AI-aided blob. Thirty years ago observers were concerned by the possibility of a dual speed internet, one for the paying consumers, the other – unsafe and dysfunctional – for everyone else. Today, the fight is not just for a better internet, but between a vastly diverse and non commercial internet — including massive datasets about poverty, climate change, social justice, geology, etc. — and the boundless AI-aided blob. It’s a different fight at a different speed.